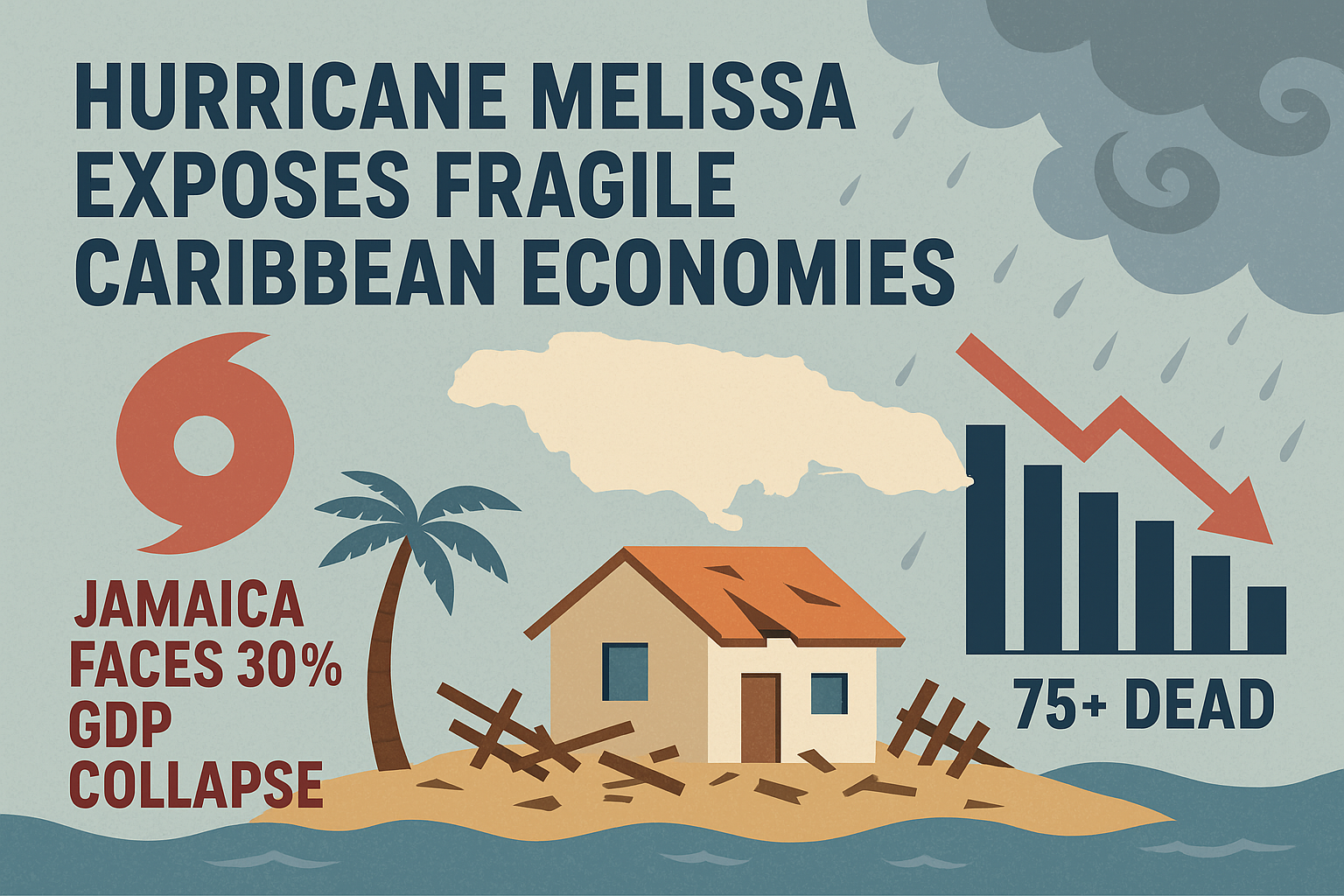

Hurricane Melissa has left a trail of destruction across the Caribbean, claiming at least 75 lives and wiping out nearly a third of Jamaica’s economy. The storm’s economic toll—estimated at 30% of GDP—marks one of the most severe climate-induced shocks in recent Caribbean history. As governments scramble for relief and the United States pledges $24 million in aid, the crisis reignites debate over climate finance, debt relief, and the urgent need to build climate-resilient economies.

The Immediate Humanitarian Crisis

The human cost of Hurricane Melissa is staggering. Beyond the 75 confirmed deaths across the region, tens of thousands remain displaced, with entire communities in Jamaica, the Dominican Republic, and Haiti reduced to rubble. In Jamaica, the storm’s eye passed directly over the island’s agricultural heartland and tourism corridor, devastating two of the nation’s economic pillars.

Port Antonio and Montego Bay, critical tourism hubs, sustained catastrophic damage to hotels, airports, and coastal infrastructure. The island’s agricultural sector—responsible for employing nearly 18% of the workforce—has been decimated, with banana plantations, coffee farms, and livestock operations facing near-total losses. Energy infrastructure suffered equally, with widespread power outages expected to persist for months as crews work to restore the national grid.

Across the wider Caribbean, the Dominican Republic’s coastal provinces reported severe flooding and wind damage, while Haiti—already grappling with political instability—faces compounded humanitarian challenges. Even Barbados, typically shielded by its eastern position, recorded significant damage to its fishing industry and beachfront properties.

Economic Fallout and Debt Pressure

Jamaica’s projected 30% GDP contraction represents an economic catastrophe of historic proportions. To contextualize the severity, Hurricane Gilbert in 1988—previously considered Jamaica’s worst natural disaster—caused losses equivalent to roughly 25% of GDP. Hurricane Melissa has eclipsed that benchmark, placing Jamaica’s recovery trajectory in uncharted territory.

The International Monetary Fund and World Bank have begun preliminary loss assessments, with early estimates suggesting total Caribbean damages could exceed $15 billion. For Jamaica specifically, the GDP hit translates to approximately $5 billion in direct and indirect losses—a crushing blow for an economy that had only recently achieved modest debt reduction progress.

“We are fighting a storm every year, but without the fiscal space to rebuild stronger,” Jamaica’s Finance Minister told Reuters in a post-storm interview, highlighting the impossible bind facing Caribbean governments.

The immediate economic consequences extend beyond infrastructure repair costs. Jamaica’s sovereign debt-to-GDP ratio, which had declined to 95% through years of fiscal discipline, is expected to surge past 120% as the government borrows heavily for reconstruction. Short-term inflation is already accelerating, driven by disrupted food supply chains and fuel shortages. With tourism revenue—accounting for 30% of Jamaica’s economy—effectively eliminated for the current season, foreign exchange reserves face acute pressure.

Climate Vulnerability and Inequality

The Caribbean’s exposure to climate disasters reflects a profound global inequity. Small island developing states (SIDS) like Jamaica contribute less than 1% of global greenhouse gas emissions yet bear disproportionate climate risks. The IMF estimates that Caribbean nations lose an average of 5% of GDP annually to climate-related disasters—a rate five times higher than the global average.

“Hurricane Melissa is a stark reminder that small economies bear the highest cost of a crisis they did not cause,” said the IMF Caribbean Division Head, underscoring the climate justice dimension of the disaster.

This vulnerability stems from geographic concentration, limited economic diversification, and constrained fiscal capacity. Unlike larger nations that can absorb regional shocks through internal resource reallocation, Caribbean islands face existential threats from single storm events. The catastrophic GDP losses force governments into impossible choices: cutting essential services, accumulating unsustainable debt, or delaying critical climate adaptation investments.

Global Response and Financing Gap

The international response to Hurricane Melissa, while well-intentioned, exposes the inadequacy of current climate financing mechanisms. The United States’ $24 million aid package represents a meaningful gesture but falls drastically short of reconstruction needs. UN emergency appeals have mobilized additional resources, and regional Caribbean development funds are being activated, yet total pledged assistance remains a fraction of actual losses.

Insurance coverage presents another critical gap. Across Caribbean SIDS, less than 25% of total disaster losses are typically insured, according to 2025 Caribbean Development Bank data. This chronic underinsurance forces governments to shoulder reconstruction costs directly, exacerbating debt distress.

“The scale of destruction demands a rethink of global climate finance, not just incremental aid,” argued a regional economist from the University of the West Indies, pointing to the disconnect between climate financing rhetoric and actual resource flows.

The disaster also arrives at a pivotal moment for global climate policy. With COP30 approaching, Hurricane Melissa strengthens calls for operationalizing the “Loss and Damage” fund framework agreed upon at previous climate summits. Caribbean leaders are demanding that wealthy nations—historically responsible for the majority of emissions—provide grants rather than loans for disaster recovery and climate adaptation.

Rebuilding for Resilience

Jamaica’s reconstruction presents an opportunity to build back better, though financing constraints threaten to derail ambitious resilience plans. Green infrastructure initiatives under discussion include decentralized energy microgrids resistant to storm damage, mangrove restoration programs to buffer coastal communities, and climate-resilient agricultural techniques.

Innovative financing mechanisms are gaining traction. Debt-for-climate swaps—where creditors forgive portions of debt in exchange for environmental investments—offer one pathway to create fiscal space for resilience projects. Catastrophe insurance reform, particularly expanding parametric insurance products that provide rapid payouts based on storm intensity rather than lengthy damage assessments, could accelerate future recovery efforts.

The Caribbean Development Bank is coordinating with multilateral institutions to design a resilient infrastructure fund, while local governments explore public-private partnerships for critical sectors like energy and water systems.

Outlook: Beyond Recovery to Transformation

Jamaica’s economic recovery timeline remains uncertain. Optimistic projections suggest a return to pre-storm GDP levels within three to four years, contingent on rapid aid disbursement, favorable weather patterns, and sustained tourism recovery. However, economists caution that without addressing underlying vulnerabilities, the Caribbean remains trapped in a cycle of disaster, debt, and delayed development.

The political implications are equally significant. Governments across the region face growing public pressure to prioritize climate adaptation, potentially reshaping electoral dynamics and policy priorities for years to come.

Hurricane Melissa ultimately demonstrates that climate disasters are not merely environmental events—they are systemic economic risks with cascading consequences for global development, financial stability, and human security. For the Caribbean, the path forward requires more than reconstruction; it demands a fundamental transformation in how the international community supports climate-vulnerable nations facing existential threats from a crisis not of their making.